How poor communication left Ruto in tight corner

Public communication by the state mostly adopts a one-way approach, resulting in incoherent government messaging.

Since the events of June 25, when Gen Z protesters overran Parliament, President William Ruto has on several occasions blamed poor communication for spurring the protests and accused his communications team of failing him.

But even after dissolving his Cabinet following the intense protests, he continued to retain the same communications infrastructure he inherited from the previous government.

More To Read

- Death toll in Elgeyo Marakwet landslide hits 37, 11 people still missing

- Elgeyo Marakwet landslide death toll rises to 35 as 16 people remain missing

- President Ruto defends teachers’ State House meeting amid backlash

- High Court halts construction of church at State House pending constitutional review

- President Ruto distributes business equipment to Nairobi youth groups

- Ruto revives ‘Hustler’ wave with youth empowerment drive ahead of 2027 polls

This is despite the fact a task force led by veteran journalist David Makali had in December 2019 presented a comprehensive report with recommendations which, if they had been implemented, could have unlocked the communications quagmire in government.

Dubbed “Winning Public Trust”, the report of the task force on the improvement of government information and communication was designed as the antidote to poor government communications which Ruto now blames for the collapse of the Finance Bill 2024.

The Makali team’s report had recommended a radical surgery of government communications, isolating the issues it needed to work on, and the structures to put in place, and, above all, proposing a mind-shift on public communication to align it to the lofty ideals of the constitution.

“The underlying mindset of government communication is out of step with the times. Despite the radical administrative and political changes introduced in 2010, the conduct of public affairs has not changed fundamentally in tandem with the requirements of the Constitution,” the task force observed.

Most public officers, the team found out, had not embraced a citizen-centric approach to managing public affairs. In the run-up to the passing of the Finance Bill 2023, the Kenya Kwanza government flatly ignored violent protests and rammed down unpopular provisions on Kenyans, among them the Housing Tax.

Again, in the lead-up to the parliamentary debate on the Finance Bill 2024, government officials largely ignored public protests on it, further infuriating citizens and setting the stage for the Gen Z protests.

“There is no evidence to suggest that public communication is ever evaluated to determine its effectiveness. In most cases, it adopts a ‘top-down’ method characterised by a one-way dissemination approach, instead of a two-way engagement model that entails creating awareness, interacting with citizens, listening and providing feedback that then informs government decisions,” Makali’s team said.

It riled the tradition of “executive orders”, directives and circulars which have tended to be “terse, instructional, and authoritative.” They are usually, and often, accompanied by threats of sanctions and punitive action for noncompliance.

When Ruto assumed office in September 2022, he adopted the same mode of giving executive orders and presidential directives which are adopted by the Cabinet, eventually finding their way to Parliament as legislative proposals.

Makali's team was not amused that there lacked a coherent, overarching government communication strategy, despite government institutions, including the Presidential Strategic Communication Unit (PSCU), professing to be strategic.

The result was incoherent government messaging that either ignored — or was often out of touch with — the daily concerns of the citizens it served, the team said. Government communication was found to be reactive and short-term, conditioned by emerging day-to-day issues rather than a longer-term vision.

The team pointed to the “contradictory or confusing” government communication on the Huduma Namba registration, the Housing Levy and the Competency-Based Curriculum as glaring examples of discordant messaging.

“This made the government appear unsure or untruthful of its objectives,” the report said.

Again, Ruto’s government inherited the same infrastructure for non-strategic communication, which did more harm than good.

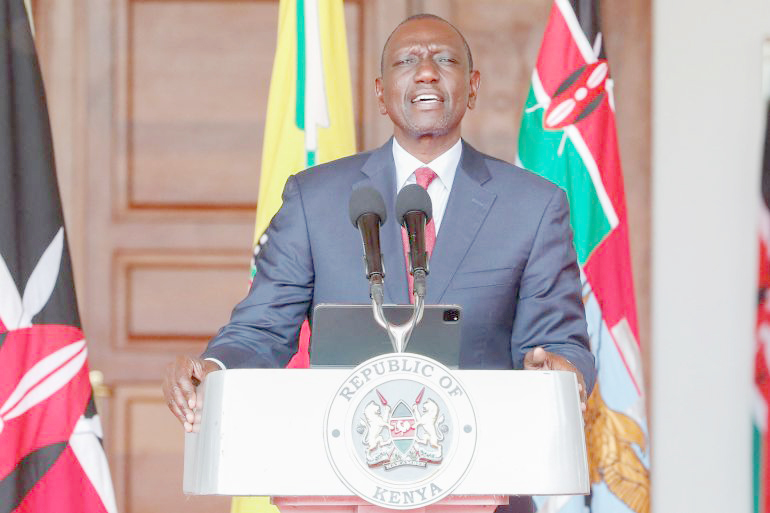

President William Ruto addresses the nation from State House in Nairobi on July 11, 2024 after he dissolved his Cabinet in the wake of nationwide protests over planned tax increase. (Photo: Thomas Mukoya/Reuters)

President William Ruto addresses the nation from State House in Nairobi on July 11, 2024 after he dissolved his Cabinet in the wake of nationwide protests over planned tax increase. (Photo: Thomas Mukoya/Reuters)

Makali’s team had analysed the communication which tended to come from PSCU, the government spokesperson and public communication in ministries, departments and agencies and which tended to be merely informational and instructional.

They were found to be “turgid and unengaging”, the common assumption in government being that citizens are a passive audience whose role is to unquestioningly act as directed.

“Even where public officials engage with citizens directly during rallies or public forums, it was perceived as being in the expectation that they would endorse a predetermined position,” the taskforce said.

A month before the demos against the Finance Bill 2024, Government Spokesman Isaac Mwaura described as “useless questions” the inquiries on expenses incurred in Ruto’s trip to the US in a chartered plane. He described those who were asking the questions as “devils” and “evil spirits”.

Makali’s team noted that going in tandem with attitude is the lack of appreciation within the government of the power of information to catalyse socio-economic progress. The predominant ethos is that information in the government’s custody is secret and withholding it from a prying public is the proper duty of a public servant.

The team condemned this as retrogressive, not in sync with constitutional provisions on access to information and the requirement that the government purposefully disseminates information of public interest.

The continued failure of Parliament and the executive to repeal sections of laws which aid this mindset adds to the confusion. These include the Official Secrets Act, Defamation Act, Preservation of Public Security Act, and the Penal Code.

Makali’s team also established that whereas the government had public communication officers well-versed in their trade, they tended to be ignored, demotivated, and under-resourced. Their roles were not quite entrenched, and they had hazy reporting lines.

Cabinet secretaries and other top government officials also tended to prefer hiring communication advisors, while also retaining regular public communication officers, thereby creating rivalry.

“They are kept away from the centre of policymaking. They are only invited at the tail end of the policy-making process, or to respond to crises. They are often out of the loop of the information they are expected to disseminate to the public,” the team noted.

The elephant in the room, Makali’s team found out, was the failure of the government to deliver public services, which undermined public trust, and eventually public communications.

Public servants were found not to appreciate the vital link between the efficacy of government actions and statements on one hand, and public confidence on the other.

Because of the conduct of its officers, ordinary citizens are unable to perceive the government and its institutions as trustworthy, honest, and acting in their best interests, thus eating away into the social capital that the government can call upon in times of crisis.

The government had also failed to embrace technology-driven communication platforms, thus missing out on feedback from the younger public.

This, the task force said, creates the impression that the government is out of touch with its constituents as it continues to use media outlets that many citizens, particularly the youth, have abandoned in favour of new platforms.

At the height of the Gen Z standoff, Ruto summoned traditional media houses to an interview at State House, where he fielded questions from top journalists. The Gen Zs hosted their own national conversation on X Spaces, forcing the president to join them, but much later.

Other weaknesses highlighted by Makali’s team included a poor information and documentation system, weak public sector support for the “Brand Kenya” concept, inordinate preoccupation with politics at the expense of service delivery, a low rating of state media, and the marginalisation of people with disabilities in information flow.

“Communication on government policies is often tied to political campaign messages, hence polarising and undermining its impartiality or credibility among segments of the public,” the team said.

Government spokesperson Isaac Mwaura speaks at a press conference on July 18, 2024, following nationwide protests over proposed tax hikes contained in the Finance Bill 2024, which was later withdrawn. (Photo: Reuters/Monicah Mwangi)

Government spokesperson Isaac Mwaura speaks at a press conference on July 18, 2024, following nationwide protests over proposed tax hikes contained in the Finance Bill 2024, which was later withdrawn. (Photo: Reuters/Monicah Mwangi)

What the team wanted done

The Makali-led task force outlined a raft of measures which would have made public communication strategic, in the true sense of the term, and effective.

At the core of its recommendation was the development of a “coherent public communication policy and plan,” which demonstrates an understanding of its audience, the new constitutional values and the expectations of the people.

The plan was to entail regular status updates on ongoing projects and reports on success stories, particularly those with a human interest focus, to demonstrate impact.

Credibility, the team said, is what will draw citizens to rally behind the government, not shallow statements or threats. Credibility was to be built through proactive communication as opposed to reactive, and the development of well-thought-out government policies.

The government was required to strengthen and rebuild the capacity of its communication workforce, rather than resorting to the quick fixes of temporary communication advisors.

The team proposed the establishment of a Government Communication Service to be run by, among others, professionals in strategic communication, journalism, development communication, and public affairs.

It said the government ought to initiate a programme to transform the public communication mindset from a government-orientated to a citizen-centred approach.

The team recommended the separation of information and public communication functions from ICT public communication. It said the amalgamation of information and communication functions with information technology ended up elevating and resourcing the ICT function at the expense of public communication.

“Public communication is, therefore, seen as a subset of the ICT function, whereas it ought to be autonomous but interdependent,” it said.

They also recommended that the government adopt digital communications and consolidate all government production and publishing agencies into one directorate.

They wanted KBC modernised and restructured to vest in it the functions of a public broadcaster. In this capacity, it would have obligations to publicise important government information and matters of public interest.

The team underscored the fact that global dynamics, coupled with an increasingly knowledgeable, restive and sophisticated population, demand that governments be swift in adapting to different circumstances.

Asked whether any of their recommendations were ever picked up for implementation, a member of the task force told The Eastleigh Voice that none had been adopted.

Top Stories Today